Women and textile. A historical relationship.

Although we can find geographical differences, international organisations estimate that around 60% of workers in the textile industry are women, reaching almost 80% in some regions (UNCTAD 2004; ILO, 2023). Many of these women occupy the most precarious positions, while the most qualified ones are taken by men. If we think about prestigious designers in the world of fashion, it is remarkable that many of the figures that come to mind are male. Although there are a much higher number of women in Fashion Schools (Pulido, 2019), their names remain diluted in the production chain (pattern makers, seamstresses, embroiderers…), and when they are recognised, they are often models. However, their presence is still the majority, and not only in modern industry. Women have been historically and, in all cultures, linked to the textile sector, whether in the domestic sphere to meet family needs or for moral issues related to “feminine aptitudes”, as well as within the productive sphere through artisanal work. Although in ancient times their presence was generally limited to work within the home or to those related to religion, such as making offerings or working in convents, already in the Middle Ages, their presence is documented as workers within guilds, especially in urban environments, but also within rural workshops in which other family members also participated (Rodríguez and Cabrera, 2019; Rodríguez, 2023). Subsequently, their incorporation into work during the Industrial Revolution began a long process in the manufacturing sector that continues to this day.

Koninklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands

“Spinning wheel” by Adolphe Weisz (ca. 1850)

Liveauctioneers

Repeatedly, this significant and valuable number of women has gone unnoticed, leaving us with only a few names in our historiography, which is currently undergoing a review from a gender perspective. Together with great more contemporary designers closely linked to the European sphere such as Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel or Mary Qant, among others, we can corroborate the presence of women in relation to great textile milestones throughout all historical periods and in various civilisations. An early example of notable relevance is that of Empress Silingshi (circa 3000 BC), who is linked to the discovery of the most valued of fabrics: silk, which, like many other textiles, would go on to have great economic and geographical and social repercussions, such as promoting economic development, but also connecting distant regions and cultures through trade routes (Quero and García, 2005; Postrel, 2020). Mythology is another important source in terms of female names and textile production, since the goddesses often weave worlds and destinies in different stories: Neith or Hathor in the Egyptian mythology, Ixchel or Coyolxauhqui in the pre-Columbian one, Nüwa in China, Sarantu in Hinduism, Frigg or the Norns in the Nordic sphere, or Athena, Hestia or the Fates in the classical antiquity, etc. Both in mythology and in the visual arts we can also observe how textiles are not only linked to the “feminine virtues’’ that concern the home and family, including domestic seclusion, marriage, temperance, care, etc. This assigned task and attribute is configured as a symbolic instrument at the service of women to achieve a certain goal. Continuing with Greco-Latin mythology as a relevant example for our case, we can mention instances in which weaving is used to resolve more mundane issues such as in the stories of Progne and Filomena, Penelope, Aracne, etc. (Dalton, 1996; Fernández, 2012). Finally, throughout history, textiles have been constituted as a practice at the service of women, valuing cultural knowledge that has implications in multiple aspects, and as a way to achieve a certain economic independence. However, it is important to keep in mind that this process of recognition of women has entailed and still entails numerous problems and challenges.

Independence and recognition or precariousness and oblivion?

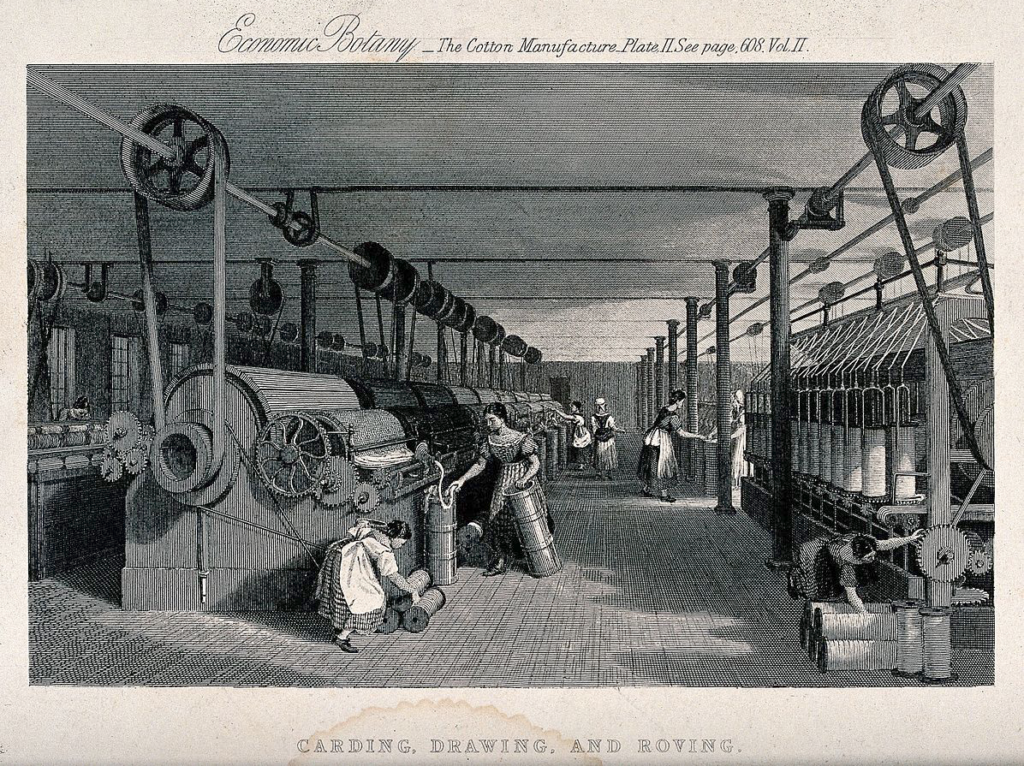

Although, as we have mentioned, the presence of women in the textile production sector has a long history, their incorporation into factory work during the Industrial Revolution represented a turning point. Prior to this, women’s work, as well as that of children, were very relevant to the family economy, but they were tasks that were carried out mostly at home and in its surroundings (Carner, 1982; Rodríguez and Cabrera, 2019). Although during the Middle Ages there was an advance with their participation in the guilds, among which their high representation in the textile industry stands out, in all of them the number of men was still higher (Rodríguez, 2023). It will be during the Industrial Revolution when the female presence is more evident in the productive sector.

The repercussions of this industrialised work on women’s lives have been widely debated to this day. On the one hand, earning income contributed to greater independence and social mobility, making it possible to put aside arduous agricultural tasks and leave the family unit. At the same time, the importance of their work for family cohesion is alluded to by preventing the man or his children from having to emigrate to obtain more income. On the other hand, reference is made to the precarious working conditions, with long hours, poor pay, physical abuse, the increase in illnesses due to the repetition of tasks in unhealthy positions, the use of harmful products or poor hygienic conditions with overcrowding, and poor ventilation and lighting (Medina-Vicent, 2014; Berwal, 2021). As we have pointed out, although if a comparative analysis is carried out between traditional female and male industrial work, women’s work may be perceived as less demanding in terms of physical effort, it also entailed numerous problems. Likewise, even within the textile sector itself, their situation was even more unfavourable. Men, who had a smaller presence compared to women and children, occupied those tasks that provided greater remuneration and a certain social prestige. But in addition, when the same work was performed, men’s salaries were higher (Arango, 1994; Medina-Vicent, 2014, Berwal, 2021). Although it has been suggested that this difference in the number of employees could be a sign of the valorisation of the knowledge and skills of the female workers, it must be taken into account that it is not the only factor to consider, since their situation of vulnerability and the availability of more abundant and cheaper labour, as shown by salaries, was decisive for their hiring (Carner, 1982; Arango, 1994; Medina-Vicent, 2014). Likewise, it is an area of work that, together with food, reflects their traditional role: clothing and nourishing (Sullerot, 1978).

Illustration of women of different ages performing household task (cooking and spinning and carding wool) from The costume of Yorkshire (1814)

British Library

Wellcome Library, London

We find examples of this dichotomy between the improvements and the issues that textile work caused for women even in the workers’ own testimonies. Thus, collections of letters such as those in Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters, 1830-1860 show very different experiences than those in others such as The Lowell Offering: Writings by New England Mill Women (1840-1845). Among all the points mentioned, economic independence is perhaps the most widely discussed in the literature as a positive aspect. However, this monetary gain did not always have an impact on the woman’s well-being. Usually, the money obtained was insufficient for subsistence and led to a precarious life. This salary was even scarce when it was part of the total family income, to which was added the salaries of the men and the children, who were also a labour force widely used in the manufacture of fabrics. In other situations, the money was used to finance the studies of the men in the family or simply did not belong to them. The response to this context of discomfort in various areas led to the emergence and organisation of numerous social mobilisations that represented important milestones in the fight for labour rights and gender equality during industrialisation. Those carried out in the countries where industrialisation and, specifically, the textile industry had greater relevance stand out, such as the northwestern United States or England. Some crucial protests were those of the Lowell Mill Girls (1834), the New York Shirtmakers’ Strike or Uprising of the 20,000 (1909) or the Lawrence Strike or Bread and Roses (1912).

Dislocated precariousness and environmental damage: The consequences of a consumption system.

Unfortunately, this situation for women within the textile industry remains a reality today, transferred to other geographical points, where insufficient social and environmental regulations favour the perpetuation of harmful practices. For the most part, relocation within the globalisation phenomenon involves countries in East and Southeast Asia (Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, etc.), but also others such as China. Progressively, this practice has been growing and expanding to new areas such as Africa or Latin America (Racz&Thews, 2021), highlighting as an exponential element the end of the Multifibre Agreement (MFA) in 2005, which regulated global textile trade since 1974 (Bhattacharya, 1999; Nordås, 2004). We must also consider that the impacts of relocation are not only focused on the production chain, but also have worrying consequences at the end of the life cycle of the item, with the creation of numerous textile landfills far from places of consumption.

“The Making of Silk Fabric” by Wang Juzheng (Northern Song Dynasty, 960–1127)

National Palace Museum, Beijing

Although there is no doubt that this situation affects the entire community, it is the poorest classes and women who experience the greatest negative impact (UNITED NATIONS, 1999), because although they have traditionally preferred jobs in the tertiary sector over industrial ones, which are often better paid (Sullerot, 1978), they are the predominant force in the textile sector and those who experience the worst conditions (Marx, 2020). As happened in Europe and the United States during the Industrial Revolution, in these countries their incorporation into the workforce means new income opportunities outside the home, but at the same time, serious situations of precariousness. Once again, female employees face excessive working hours, disproportionately low salaries, lack of social security, repetitive tasks and a highly dangerous work environment, where the number of substances harmful to health and the environment is very high (Worker Diaries; Labor Behind the Label; Fashion Revolution, n.d.). According to research, workers in the textile industry have a greater predisposition to various types of occupational cancer, with a predominance of lung or bladder cancer (Singh and Chadha, 2016). This situation of unrest is often ignored and international reports continue to document a worrying general situation (ILO, 2014; 2023), despite instances of massive attention with media covered cases such as the fire at the Tazreen Factory in Bangladesh or the collapse of Rana Plaza, in the same country. The 2019 pandemic also revealed another reality that many women faced in the textile sector, with a predominance of temporary contracts that leaves them in a situation of vulnerability in periods of maternity, illness, or instability, as happened with COVID-19, when a large number of workers did not receive pending salaries or compensation due to the high number of sudden dismissals (ILO, 2020; WRC, 2021).

The pressure only increases because of an increasing demand, predominantly from Europe and the United States, which insist on increasingly shorter production times and lower prices. Although the clothing industry is the highlight of this issue, the pressure on production also includes those textiles intended for home decoration, which often reflect an increasingly changing fashion. Traditionally, trends used to spread from the most privileged to the least privileged classes, with differences between classes, roles, and functions, more gradually, but in recent decades there have been accelerations in these rhythms, which have direct implications for production. The growing relevance of the individual compared to the collective in contemporary times and the increase in the middle classes means that the “downward filtering” has been leaving room for new forms of diffusion, much more dynamic with theories such as Wiswede’s “virulence” (Barreiro, 2006) in an increasingly volatile environment. Thus, we’ve gone from changes in fashion with extended periods of time and therefore with more spaced collections, to greater dynamism and multiplicity. Furthermore, fashion not only changes more quickly, but it is plural, providing different options depending on the taste of the individual (Lipovetsky, 1990), or the interest of belonging to a certain group, as Maffesoli explains in The Times of the Tribes. Chain production, of the Fordism characteristic of the Industrial Revolution, leaves room for a more diverse but equally excessive production, post-Fordism, or flexible production. That is, mass production, but not so much in series. In this context, ICTs play a crucial role, shaping the Third Industrial Revolution, with a growing capacity to process information thanks to advances in computing and thus generate new collections in line with market fashions. The “Just in time” (JIT, n.d.) criterion would define the new form of textile operability, reducing the quantity of each of the models, but launching different collections more frequently to reduce the risks of losses associated with larger collections and a longer manufacturing process, taking over a market with increasingly varied tastes. The sales would close a production strategy that ensures that the entire stock is sold, providing disproportionately reduced prices against which it is difficult to compete, thanks to the high profit margin due to the reduced production cost (Barreiro, 2006).

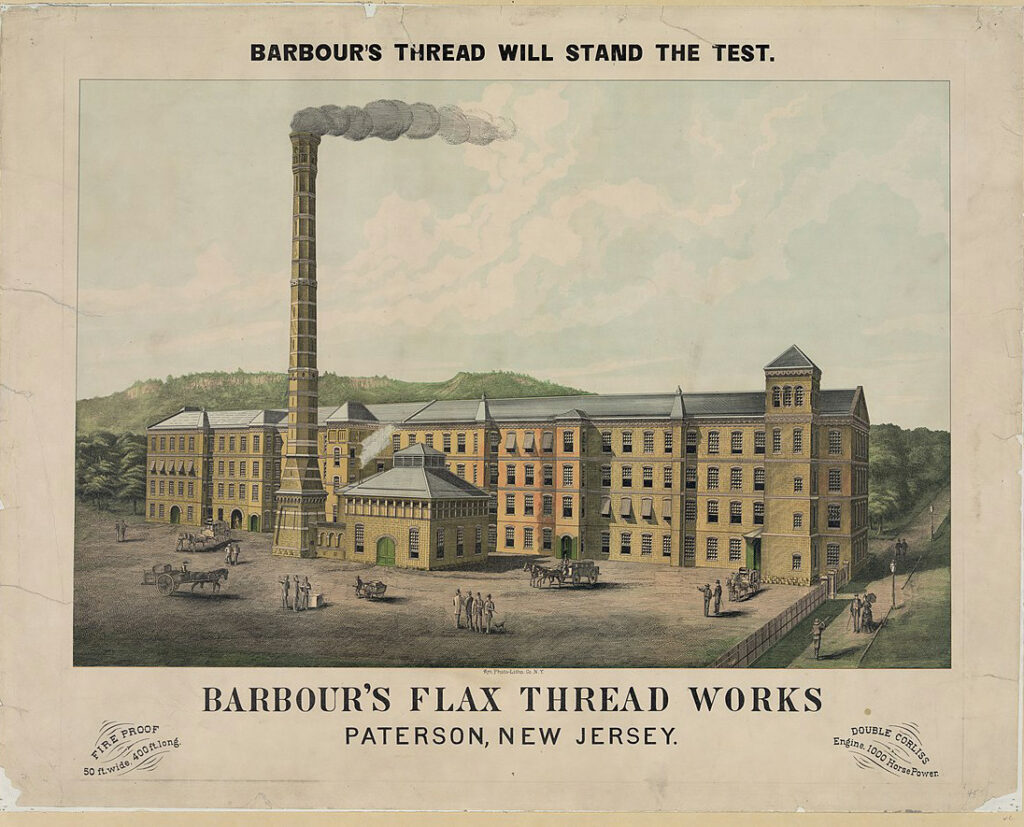

Barbour’s flax thread works

United States Library of Congress’s

Along with relocation, diversification of production is a key element to cover this type of market. Through small factories, with subcontractors in charge of different collections, garments, or components, it is guaranteed to adjust the production scale to the various demands. Garments are no longer only manufactured far from the points of consumption, but the production of the same garment involves a multiplicity of productive units and places, even from the raw materials themselves. For example, before the garment is made, cotton has already crossed international borders (USDA, 2009; Racz&Thews, 2021). This system brings with it new complexities in terms of regularisation and deprecariousness of women’s work, because although there are controls, these are usually oriented towards the largest companies and it is precisely women, especially those from lower social classes, who work for smaller companies (ILO, 2023).

A conscious textile production: Crafts and sustainability as a proposal for the present and future.

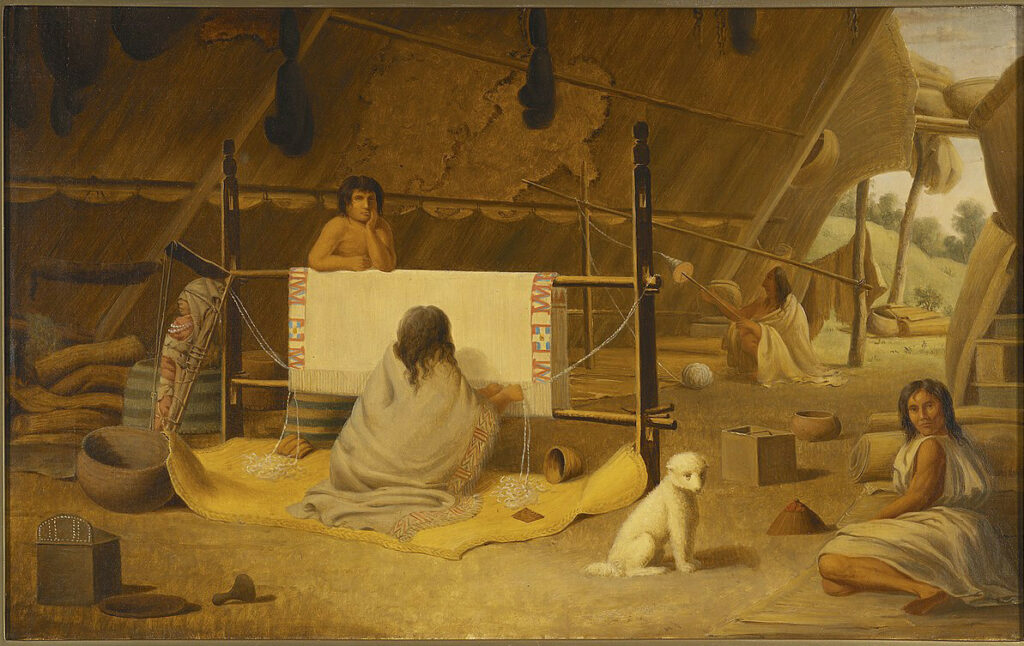

“A woman weaving a blanket” by Paul Kane (ca. 1850)

Royal Ontario Museum, Gallery of Canada

Given the enormous social and environmental impacts of conventional textile production, we should ask ourselves what opportunities the production and sale of artisanal textiles has to offer. In recent years there has been renewed interest in crafts from multiple perspectives. Within the textile sector, numerous projects related to women are being carried out, eminently focused on rural areas and developing regions, where crafts continue to be an important source of income for women and their families, especially in Africa and some areas of Latin America. Craftsmanship is thus seen as a way to address current global problems and orient us towards sustainability in its triple aspect: social, environmental, and economic. In Europe, this recovery is also mainly oriented to rural areas, where various conscious practices have been preserved in greater numbers: ways of doing things, knowledge about the environment, materials, or the characteristics of objects necessary to extend their useful life. In short, a heritage to look at to guide the future, valuing women and energising rural communities in the different territories.

In addition to the topics addressed in previous sections linked to social sustainability, to look for alternatives from craftsmanship and the territory, it is necessary to consider textiles from a holistic perspective, paying attention to the environmental effects of the current model. That is, the impacts affect the environment, and therefore have repercussions on human beings as part of the ecosystem in which they live. A clear example is the impact of climate change on the natural resources on which women depend for textile production, with extreme phenomena and changes in weather patterns (UN WomenWatch, 2009).

Traditional textile production implied -and still implies- a deep knowledge of local natural resources, such as plant and animal fibres for the manufacture of threads or dyes. Already from the beginning of production, with the obtention of resources, these textile practices resulted in a configuration of the rural territory through different artisanal cultural landscapes (Larrain and Tapia, 2022). Like this, a type of livestock dedicated to obtaining wool will create a specific space distribution and maintain a specific type of vegetation. An agricultural plantation will do the same, such as flax, hemp or cotton, or the plants necessary for their dyeing grown in some rural areas of Europe, such as madder or lavender. Although any action has an impact on the environment, these livestock and agricultural practices were conceived in a sustainable way, using, for example, techniques such as grazing or rotational crops, influencing the structure of the soil, vegetation, and biodiversity. Also, prior to the Industrial Revolution, the treatment of materials was minimal and the amount of energy used was much lower. However, these ways of doing things have been increasingly relegated and replaced by new activities within the linear economy.

Although it is a very broad topic with many particularities, we will analyse from a general perspective the negative consequences that the production of a contemporary textile object can generate in the current system and, from this, the possibilities that craftsmanship has to offer. Firstly, the extraction of raw materials for an exorbitant demand entails the overexploitation of natural resources, often in areas far away from consumption points. Subsequently, with its transformation or with the production of synthetic materials required to produce fabrics, many pollution emissions are released into the atmosphere, but there is as well as an impact on water, both due to its high use and the harmful substances that are discharged. We must consider that the production of a garment not only includes the making itself, but also the aesthetic accessories or dyeing, one of the processes with the greatest environmental consequences. The shipment of these goods, considering the relocation and diversification of production, is increasing, in turn generating an environmental footprint with packaging and transportation. During its useful life, the consequences on the environment are related to issues such as excessive washing and the use of detergents that also end up in the water, along with the microfibers that are shed. Finally, in the contemporary linear economy, textiles are discarded, with difficult recycling as numerous components are used that cannot be separated and usually end up incinerated or accumulated in landfills located in the poorest countries (Carrera, 2017).

Faced with this culture of obsolescence, crafts can be an alternative, enrolling in a circular economy focused on reducing, reusing, recycling, and recovering to minimise waste and promote efficiency in the use of natural resources. However, we must approach this new perspective with better judgement, because as Donella and Denis Meadows already showed in 1972 in their book The Limits of Growth, “in a finite world, growth cannot be infinite” and with the current exponential growth of population and consumption, many of the a priori sustainable systems may end up not being so. An illustration of the problem in textiles is the case of dyes. Already in the Middle Ages, with a much smaller number of people, the harmful effects of dye shops were documented, with discharges into riverbeds or a large consumption of firewood to obtain energy (Rodríguez, 2023). Despite being more respectful in general, natural dyes also impact the environment, for example, in the areas reserved for their cultivation, the energy for their treatment, or in some cases, with the elements used to fix the pigment, etc. In short, any element, if used massively, may not be sustainable. This is one of the key points in which the recovery of textile crafts must be done consciously, from a holistic perspective, considering the teachings of the past and the discoveries of the present, while being accompanied by a change of consumer mentality. To achieve this, some intrinsic characteristics of craftsmanship can be highlighted as a positive, differentiating attribute and as an attraction. The most important one is the value of quality and durability, with pieces made with care, guaranteeing a longer useful life and timeless aesthetics. This fact, initially favourable, brings with it two indirect issues that must be also considered: the production of this type of garments is directly opposed to a manufacturing and consumption model where the benefit lies in continuous purchasing, in addition to the low salaries of the producer. If the number of productions is reduced in line with a reduced need to purchase products, jobs would also be lost. However, this balance could be restored if the value of each garment increased, which would result in better remuneration for the producer, even if fewer units were sold, something also in line with production times. At the same time, the consumer should adopt a change of mentality in which, despite a greater initial outlay, the durability of the product and long-term savings should be valued and thus differentiate real need from created need.

Related to the social sphere, another of the virtues of craftsmanship is resistance to cultural homogenization in a globalised world. As we have seen, the concept of fashion has changed over time, and today, personal taste has become relevant. The theory of “hybrid identities” (Hall, 1997) exposes how despite the existence of globalising tendencies, they share space with a reinforcement and recovery of the local produce. But often these artisanal spaces are taken over by large textile companies, taking away a resource that belongs to the artisans. In a saturated market with aggressive marketing, even when the local produce becomes important, its creations are made invisible by the recreations of fast fashion. In this sense, rural areas can be presented as an opportunity for promotion, an empty space, where craftsmanship is established as an identifying and energising element. The dissemination of crafts could go hand in hand with renewed interest in rural areas with booming phenomena such as rural and experiential tourism linked to activities and the landscape. Another promotional element related to the social sphere is the dissemination of the ethics with which the creations are made, which must be coupled with the dissemination of the harsh reality of the textile industry for women and the environment. In both cases, it becomes essential to develop mechanisms that empower the consumer to discern between authentically artisanal products and those that use strategies such as “solidarity marketing” (Barreiro, 2006), greenwashing or imitation of artisanal production.

Wherewithart

Faced with these great challenges, female artisans have been developing ways of cooperating that facilitate their insertion into the market and an increase of their recognition. The United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (INSTRAW, n.d.) highlights that artisanal textiles are often linked to cultural and political resistance movements led by women in local communities, developing various projects at a global level, although many of them focused on Africa or Latin America, and, to a lesser extent, in Asia. This cooperative work facilitates their positioning as artisans, as well as social cohesion between women and the community in general. For example, through tasks such as spinning wool, a space of time usually shared with other heritages such as music, dance, or stories. Textiles are thus a common thread between different material and intangible heritages. We have another example of its great influence in the landscape, in this case through the ornamental motifs that decorate traditional architecture and that are often taken from fabrics, or with specific architectural types such as the fulling mill that are distributed in the territory. Furthermore, weaving has been an important means of transmitting stories, traditions and messages within a specific community or ethnic group (Latin American “arpilleras”, the American Quilt, or the “women’s language” of the Miao tribe in Asia) and it also plays an important role in religious ceremonies and rituals.

However, today, textiles are culture, but also industry and economy. Therefore, fusing craftsmanship with contemporaneity is an innovative solution to delve into. Along these lines, it is crucial that this collaboration is carried out with deep respect for artisans, ensuring equity and adhering to best practices, as dictated by the guidelines of international organisations such as the UNESCO Meeting between Designers and Craftswomen (2004). If done correctly, these working methods allow traditional knowledge to be merged with new approaches, such as the mechanisation or digitalisation of certain phases, market and consumer analysis, graphic design and dissemination, or the incorporation of new concepts such as transparency in the supply chain or the use of R&D&I or recycling materials, where women have been pioneers in the implementation of avant-garde technologies and practices (Fashion Revolution, n.d.), as well as new paths within contemporary art.

For a well-understood sustainable development.

Through this text, the complex interactions that the textile-woman bond has, as well as the repercussions of textiles in the social and cultural, economic, and environmental spheres, have been outlined. We have also considered the importance of both textiles as an isolated element and its implications in other cultural manifestations, material and immaterial from a cultural perspective. Starting from this integrative vision and the important challenges we currently face, the need to adopt solutions to problems with equally integrative approaches that promote sustainable development of communities is highlighted, while bringing special attention to women. But what is sustainable development? A term that has been used so frequently and lightly in recent years that its meaning has often been distorted and obscured. Therefore, we must remember that sustainable development must be understood and applied not only as exponential growth, in which the economic plays a predominant role, but as an evolution, an improvement that goes beyond the quantitative, focusing on the qualitative, (Cañal and Vilches, 2009), and considering the social and environmental aspects together, as already included in the Brundtland Report of 1987.

references

Arango, Luz Gabriela. “Industria textil y saberes femeninos”. Historia Crítica 1 (9), (1994): 44-49.

Barreiro, Ana Martínez. “La difusión de la moda en la era de la globalización”. Papers: revista de sociología, (2006): 187-204.

Berwal, Rekha. “Women’s Contribution In The Textiles Industry: A Historical And Contemporary Analysis”. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT) 9, no. 1 (January 2021): 4922-4930.

Bhattacharya, Debapriya. The post-MFA challenges to the Bangladesh textile and clothing sector. Trade, sustainable development and gender, 1999.

Cañal, Pedro and Amparo Vilches. “El rechazo del desarrollo sostenible: ¿una crítica justificada?”. Enseñanza de las Ciencias VIII, Congreso Internacional sobre Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias, (2009): 676-679.

Carner, Françoise. “La familia y la Revolución industrial”. Diálogos: Artes, Letras, Ciencias Humanas 18(2), 104, (1982): 20-28.

Carrera Gallissà, Enric. “Los retos sostenibilistas del sector textil”. Revista de Química e Industria Textil 220, (2017): 20-32.

Dalton, Margarita. Mujeres, diosas y musas: tejedoras de la memoria. Colegio de México, Programa Interdisciplinario de Estudios de la Mujer, 1996.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Economic Research Service. Briefing Rooms: Cotton, November 2009.

Encuentro entre diseñadores y artesanos: guía práctica. Craft Revival Trust (India) & Artesanías de Colombia, 2005.

Fashion Revolution. “We are Fashion Revolution”. Accessed March 27th, 2024. https://www.fashionrevolution.org

Fernández Guerrero, Olaya. “El hilo de la vida. Diosas tejedoras en la mitología griega”. Feminismo/s 20, (2012): 107-125.

Global Worker Dialogue. “About us”. Accessed March 27th, 2024. https://workerdiaries.org

Hall, Stuart. “The Question of Cultural Identities’’. In: Hall, Stuart, et al. Modernity: An introduction to Modern Society. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997.

ILO – International Labour Organization. Salarios y tiempo de trabajo en los sectores de los textiles, el vestido, el cuero y el calzado. Organización Internacional del Trabajo, Ginebra, 2014.

ILO – International Labour Organization. “Info Stories. Cómo lograr la igualdad de género en las cadenas mundiales de suministro de la industria de la confección”. March, 2023. https://www.ilo.org/infostories/es-ES/Stories/discrimination/garment-gender#the-global-garment-industry-a-bird%E2%80%99s-eye-view-(1)

Instraw, United Nations. “New Virtual dialogue on gender and DDR”. Accessed March 27th, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20100701120540/http://www.un-instraw.org/

International Labour Organization. “Gendered impacts of COVID-19 on the garment sector”. November, 2020.

Labour behind the label. “Who are we and why do we have to exist”. Accessed March 27th, 2024. https://labourbehindthelabel.org

Langemeier, Autumn L. Fashion in Focus: Women and Textiles in Rural America, 1920-1959. University of Nebraska at Kearney, 2021.

Larrain, Claudia and Josefina Tapia. “Paisaje cultural artesanal”. ARQ 110, (2022): 84-91.

Lipovetsky, Gilles. El imperio de lo efímero. La moda y su destino en las sociedades modernas. Barcelona: Anagrama, 1990.

Marx, Sina. Wages and Gender-based Violence. Exploring the connections between economic exploitation and violence against women workers. Fashion Checker and Clean Clothes Campaign, October 2020.

Meadows, Denis, Donella Meadows and Jørgen Rangers. Los límites del crecimiento. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1972.

Medina-Vicent, María. “El papel de las trabajadoras durante la industrialización europea del Siglo XIX. Construcciones discursivas del movimiento obrero en torno al sujeto “mujeres”. Fórum de Recerca 19, (2014): 149-163.

Naranjo Pulido, Laura Patricia. “La cultura y el género: factores de influencia en la elección por la carrera de diseño textil y de indumentaria (2015)”. Cuadernos Del Centro De Estudios De Diseño Y Comunicación 65, (2019): 154-163.

Nordås, Hildegunn Kyvik. Global Textiles and Clothing Trade Post the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing. World Trade Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

Postrel, Virginia. “El tejido de la civilización. Cómo los textiles dieron forma al mundo”. Siruela, (2001, ed. castellano). Trad. Lorenzo Luengo, 2020.

Quero, Carmen García-Ormaechea. La ruta de la seda. Departamento de Historia del Arte III Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2005.

Racz, Kristof and Martje Theuws. Aspectos de género en la industria de la indumentaria latinoamericana. Informe SOMO (Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations). Amsterdam: Oxfam Novib Linkis, 2021.

Rodríguez Peinado, Laura. “Trabajo Textil femenino en la Edad Media: Ocupación señorial y oficio profesional”. Asparkía. Investigació Feminista 42, (2023): 103–125.

Rodríguez Peinado, Laura y Ana Cabrera Lafuente. “Mujer y actividad textil en la Antigüedad y la Edad Media temprana”. En Conesa Navarro, Pedro David, Gualda Bernal, Rosa María y José Javier Martínez García (coords.) Género y mujeres en el Mediterráneo antiguo. Iconografía y literatura, Universidad de Murcia, (2019): 361-373.

Singh, Zorawar and Pooja Chadha. “Textile industry and occupational cancer”. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology 11, 39 (2016).

Sullerot, Evelyne. “La Mujer y el trabajo en Europa”. El Correo de la UNESCO: una ventana abierta sobre el mundo XXXI, 11, (1978): 18-22.

United Nations. Trade, sustainable development and gender. Conference On Trade and Development. United Nations, New York and Geneva, 1999.

WomenWatch. “Fact Sheet Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change”. Accessed March 27th, 2024. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/

Worker Rights Consortium. “Fired, Then Robbed: Fashion Brands’ Complicity in Wage Theft During Covid-19”. December, 14, 2021.